World Sickle Cell Day

July 20, 2012

Mohamed Akram-Abdulla MBBS, MRCP (UK) [Maldives Medical Association Contribution]

A United Nations resolution made 19th June as World Sickle Cell Day (WSCD). Globally there are probably over 2 million people who are affected with the disease. Though I have no statistical evidence, it is likely that a number of individuals in the Maldives are affected by this painful, life shortening illness. This disease not only carries a high morbidity and mortality with it but also the emotional and financial burden is huge. As health professionals it is incumbent upon us to make sure we support these individuals as best as we can. The least, perhaps, we could do for them is making sure we diagnose them early and correctly, offer the right treatment and provide them the right information. The aim of the summary review below is to increase awareness among the medical community about the condition and the specific therapies that are available today. It is not possible to cover all aspects of the disease however I hope it gives some insight regarding this gruesome disease.

Sickle cell disease (SCD)

Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) and its variants are genetic disorders. It is an autosomal recessive disorder first described by Herrick in 1910. This occurs due to a mutation in the Haemoglobin, called Haemoglobin S (HbS). SCD causes significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in people of African and Mediterranean ancestry. Morbidity, frequency of crisis, degree of anemia, and the organ systems involved vary considerably from individual to individual. The most common form of the disease is the HbSS variant. This essentially means the individual has tow abnormal haemoglobins which then leads to precipitation of the disease. Though almost all suffer from various degrees of clinical symptoms the severity of the symptoms vary hugely form individual to individual and at times can be a diagnostic challenge specially in places where medical facilities and diagnostics are readily not available. Almost half of the individuals with the homozygous status of the disease experience vaso-occlusive crisis. But the frequency and the severity of the crisis again vary from individual to individual. Some have more 6 o more such events a year while some may have a few or none. Most people with HbSS suffer from low level chronic pain mainly in the bones and in some individuals this may be the only presenting symptoms of the disease. A crisis may present as worsening of this pain.

A person is said to be a carrier when the individual has an HbS along with normal adult hemoglobin (HbA). These individuals usually do not manifest clinical symptoms. However when an HbS is mixed with another form of abnormal hemoglobin then they may suffer from milder form of the disease on one such example is when HbS is mixed with beta-thalassemia, known as sickle beta thalassemia.

Epidemiology

The disease is found worldwide but prevalence of the trait is as high as 30% in several parts of Africa. It is also found in some parts of Sicily, Greece, Turkey and India. The mutation that results in HbS is believed to have originated from India and Africa. This is perhaps due to the survival advantage that the heterozygote forms offer against plasmodium falciparum, a form of Malaria. I have no doubt the disease exist in the Maldives though we are short of any statistical figures.

Disease characteristics at various ages

Haematological abnormalities can be noted as early as 10 weeks but clinical manifestation often do not occur until later part of the first year when the fetal Hb decline and this allows the abnormal HbS to cause clinical symptoms. SCD disease then persist life long though it is believed that the painful crisis decrease after 10 years but complication rate increases thereafter. The mean age patients with SCD develop end-satge renal disease is about 23 years and median life expectancy even with dialysis is about 27 years.

How do patients with SCD present.

General Overview — The clinical manifestations of sickle cell disease vary markedly among the major genotypes. The term sickle cell disease s generally used to describe all of the conditions associated with the phenomenon of sickling, whereas the term sickle cell anaemia is generally used to describe homozygosity for haemoglobin S (ie, Hb SS). The disorder is most severe in patients with homozygosity for HbS. Among patients with sickle cell-beta thalassemia, the disease varies with the quantity of hemoglobin A, often being quite severe in patients with sickle cell-beta (0) thalassemia and less severe in patients with sickle cell-beta (+) thalassemia. It is best to describe the manifestations of the disease under the following sub headings.

Chronic pain in SCD

Many individuals with SCD experience chronic low-level pain, mainly in bones and joints. Intermittent vaso-occlusive crises may be superimposed, or chronic low-level pain may be the only expression of the disease.

Anaemia

This is a universal feature. In the right context if a child is found to be anaemic the possibility of SCD or one of its variants such as sickle cell beta thalassemia should be explored. Most tolerate the anaemia very well and are not symptomatic with daily activities of living but the gie away would their low tolerance to exertions compared to their healthy peers.

Aplastic crisis

A serious complication s caused by infection with Parvovirus B-19 (B19V). This virus causes fifth disease, a normally benign childhood disorder associated with fever, malaise, and a mild rash. This virus infects the RBC precursors and can cause an acute drop in haemoglobin in patients with SCD.

Splenic sequestration

This condition occurs when spleen destroys the abno ormal RBC at a very rapid rate and causes very acute drop in Hb. This also results in progressive splenomegaly. This is a medical emergency requiring transfusion support, close monitoring and often splenectomy in older children.

Infection

Organisms that pose the greatest danger include encapsulated respiratory bacteria, particularly streptococcus pneumonia. The mortality rate of such infections has been reported to be as high as 10-30%. Consider osteomelitis when dealing with a combination of persistent pain and fever. Bone that is involved with infarct-related vaso-occlusive pain is prone to infection. Staphylococcus and Salmonella are the 2 most likely organisms responsible for osteomyelitis.

During adult life, infections with gram-negative organisms, especially Salmonella, predominate. Of special concern is the frequent occurrence of Salmonella osteomyelitis in areas of bone weakened by infarction.

Effects on growth and maturation

During childhood and adolescence, SCD is associated with growth retardation, delayed sexual maturation, and being underweight. Growth delays during puberty in adolescents with SCD are independently associated with decreased Hb concentration and increased total energy expenditure.

Hand-foot syndrome

Figure 1: Ischemia leading to pain and swelling of hand (Ref: medindia.net)

The syndrome develops suddenly and lasts 1-2 weeks. Hand-foot syndrome occurs between age 6 months and 3 years; it is not seen after age 5 years. This is a dactiliytis and presents with severe pain along with swelling of dorsum of hands and feet.

Acute chest syndrome

Acute chest syndrome is a medical emergency and must be treated immediately. This carries significant risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Acute chest syndrome probably begins with infarction of ribs, leading to chest splinting and atelectasis. Because the appearance of radiographic changes may be delayed, the diagnosis may not be recognized immediately. Other conditions to think of are pulmonary infarction and fat embolism resulting from bone marrow infarction.

Central nervous system involvement

Central nervous system involvement is one of the most devastating aspects of SCD. Stroke affects 30% of children and 11% of patients by 20 years. It is usually ischemic in children and hemorrhagic in adults. Hemiparesis is the usual presentation but may present with other defects. Convulsions are frequently associated with stroke. Hemorrhagic stroke is associated with a mortality rate of more than 29%.

Cardiac involvement

The heart is involved due to chronic anemia and microinfarcts. Haemolysis and blood transfusion lead to haemosiderin deposition in the myocardium. This significantly Increases the risk of dilated cardiomyopathy.

Renal involvement

The kidneys lose concentrating capacity. Isosthenuria results in a large loss of water, further contributing to dehydration in these patients. Renal failure may ensue, usually preceded by proteinuria.

Eye involvement

Proliferative retinitis is common in SCD and may present with loss of vision.

Leg ulcers

These are often chronic and painful. Circulation is poor and increases risk of infection

Priapism

Priapism, defined as a sustained, painful, and unwanted erection, is a well-recognized complication of SCD. Priapism tends to occur repeatedly. It may lead to impotence. Mean age at which priapism occurs is 12 years, and, by age 20 years, as many as 89% of males with SCD would have experienced one or more episodes of priapism. Priapism can be classified as prolonged if it lasts for more than 3 hours or as stuttering if it lasts for more than a few minutes but less than 3 hours and resolves spontaneously. Prolonged priapism is an emergency that requires urologic consultation.

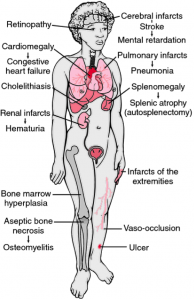

Figure 2: Clinicopathologic findings in sickle cell anaemia. The findings are a consequence of infarctions, anaemia, haemolysis, and recurrent infection. From Damjanov, 2000. (Ref: http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com)

Pulmonary hypertension

Various studies have found that more than 40% of adults with SCD have pulmonary hypertension that worsens with age. This incidence is as high as 30%. This is associated with high mortality in adults.

Diagnosis of sickle cell syndrome

Prenatal Testing

The sickle haemoglobin diseases (ie, sickle cell anaemia, haemoglobin SC disease, sickle cell beta thalassemia) are chronic, debilitating and sometimes fatal. The severe clinical nature of these diseases, particularly SCD and sickle cell beta thalassemia, and the absence of curative therapy are the primary stimulants for the development of foetal sampling and DNA-based diagnostic methodology. Couples at risk should be offered haemoglobinopathy testing early in pregnancy and the opportunity for prenatal diagnosis where appropriate.

Newborn Screening

Infants with SCD generally are healthy at birth and develop symptoms only when foetal haemoglobin levels decline later in infancy or early childhood.

The goals of newborn screening are

- Early recognition of affected infants

- Early medical intervention to reduce morbidity and mortality, particularly from bacterial infections

- Institution of regular and ongoing comprehensive care through a multidisciplinary sickle cell clinic, in collaboration with the primary care physician, whenever feasible

- Access for families of children with SCD to accurate information about the diagnosis, clinical manifestations, treatment options, and age-appropriate anticipatory guidance toward the management of these emerging issues.

- Older children and adults

The purpose of correct diagnosis in this age group is to identify patients who need therapy for sickle cell disease and counselling for the disease or the trait. Despite newborn screening, many patients with sickle cell disease may be undiagnosed, in part due to immigration of young, unscreened patients from other countries.

A brief look at blood abnormalities

Typical baseline abnormalities in the patient with SCD include:

- Hemoglobin level is 5-9 g/dL

- Hematocrit 17-29%

- Total leukocyte count is elevated to 12,000-20,000 with a predominance of neutrophils

- Platelet count is increased

- ESR is low

- The reticulocyte count is usually elevated, but it may vary depending on the extent of baseline hemolysis

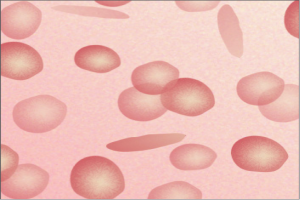

- Peripheral blood smears demonstrate target cells, elongated cells, and characteristic sickle erythrocytes

- Presence of RBCs containing nuclear remnants (Howell-Jolly bodies) indicates that the patient is asplenic

Figure 3: The HbS gene causes the red blood cells to become abnormally crescent-shaped and rigid, like sickles used to cut wheat. (Ref: understandingrace.org)

Results of hemoglobin solubility testing are positive, but they do not distinguish between sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait.

There are several other investigations that will need to be carried out during the complete work up but once the diagnosis is made it is important to tailor the investigations to answer most pressing clinical problem.

Specific therapies for Sickle cell disease

The only cure for the disease at present time is haematopoetic cell transplant (bone marrow transplant) and hydroxyurea is the only major medical modality with proven efficacy in patients with frequent symptoms related to SCD

Summary of treatment recommendation

Children and adults

In children older than two years of age and adults with sickle cell disease who have frequent painful episodes, severe symptomatic anemia, or a history of acute chest syndrome or other severe vasoocclusive events, treatment with hydroxyurea is recommended (evidence Grade 1A). This agent should be continued for as long as it is tolerated and effective.

Very young children

Very young children (ie, 9 to 18 months of age) with SCD, independent of disease severity, be treated with hydroxyurea . Compounding pharmacy support is required because a liquid form of the medication is not yet available. The evidence was recently downgraded from 1A recommendation to a 2A suggestion because of the lack of long-term safety data for children in this age range.

There is no information on the safety and efficacy of hydroxyurea in children younger than nine months of age. However, given the high prevalence of splenic damage prior to nine months of age, the use of hydroxyurea in children younger than nine months of age with symptomatic disease is recommended (The evidence is weak Grade 2C). In children who have been started on hydroxyurea in this age range who remain asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, hydroxyurea should be continued indefinitely, (Evidence Grade 2B)

Children and adults with minimal disease activity

In adults and children who are older than 18 months of age and who have been asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic without treatment with hydroxyurea, should not be started (Evidence Grade 2C).

Data are sparse concerning its benefit, however addition of erythropoietin in patients not responding to hydroxyurea alone is often standard practice (Evidence Grade 2C).

Transfusion with packed red blood cells should be given when symptomatic anaemia is present.

Monitoring

During treatment with hydroxyurea patients should have regular FBC, with red cell indices, white blood cell differentials, reticulocyte percentage. Renal and liver function should be monitored regularly. Childbearing age females should have a pregnancy test before starting the medication and appropriate contraceptive advice should be offered.

Transplantation — Indications for marrow transplantation in patients with sickle cell disease have included the presence of severe debilitating clinical events such as stroke, recurrent acute chest syndrome, and recurrent painful vaso-occlusive crises. This procedure, which can be associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, has been generally limited to children and young adults with an HLA-matched sibling donor.

Novel therapies

Gene Therapy — Although still experimental, gene therapy has the potential to cure SCD Expression of the human sickle gene in transgenic mice and creation of plasmids with the human beta globin locus are examples of the possible feasibility of this approach. This approach is believed to increase the foetal Hb and as we know high levels of foetal Hb prevents sickling.

Nicosan — The only one herbal agent tested to date, nicosan, has proved to have an efficacy/toxicity ratio sufficiently high to merit testing in clinical trials. Nicosan is a plant extract that has been successfully used in Nigeria to prevent painful crises associated with SCD .The exact mechanism of action, active ingredient(s), and long-term side effects are unknown, nicosan inhibits sickling in vitro as well as in vivo in a transgenic mouse model of SCD. Nicosan has been granted orphan drug status by the United States FDA and the European Medicine Evaluation Agency, but there is no commercial supplier of the agent.

Acute pain plan

Every adult with sickle cell disease (SCD) should have an established pain plan tailored to his/her individual needs. This plan should instruct the individual how to appropriately manage mild, moderate, and severe pain, with a pre-defined threshold for the use of opioids and when to contact health care providers. Optimally, an individualized pain plan has been established in the ED with the haematology team.

Pain management in the A&E

For patients presenting to the A&E with acute pain crisis

- Intravenous morphine (0.1 to 0.15 mg/kg), with reassessment of pain in 15 to 30 minutes after the dose is administered.

- Patients with severe pain may require repeated doses of intravenous morphine 0.02 to 0.05 mg/kg every 20 to 30 minutes to achieve pain relief.

- If adequate pain relief is achieved with a single dose, consider discharge to home on long-acting opioids with a prescription for medication for breakthrough pain.

- If the individual does not typically require long-acting opioids at home, discontinue the long-acting opioids when the pain event subsides.

- Hospitalization should be considered for around-the-clock parenteral analgesics if more than two doses of morphine or hydromorphone are required to control the pain episode.

Inpatient management of pain crisis

- IV opioids with a patient controlled Anaesthesia (PCA) should be considered as an initial option.

- For initial inpatient care in patients who are not taking opioids routinely, use intravenous morphine sulphate at 0.1 to 0.15 mg/kg every two hours or intravenous hydromorphone, 0.015 to 0.02 mg/kg IV every three hours. Reassessment is required 15 to 30 minutes after each dose is administered.

- When pain relief is not achieved with intermittent dosing of opioids, use continuous infusion of morphine or hydromorphone, preferably with a patient controlled analgesia (PCA) program that allows additional demand dosing.

- In the setting of significant renal or hepatic dysfunction, fentanyl is the IV opioid of choice.

- Use of benzodiazepines for insomnia should be avoided as they may predispose the patient to respiratory depression.

- Use of phenothiazines for nausea should be avoided as this may potentiate sedative effects. In the event that nausea is associated with opioid administration, odansetron is recommended as the antiemetic of choice.

- Ensure patients are well hydrated.

Variant sickle cell syndromes

There are several sickle cell variants linked to sickle cell gene in compound heterozygosity with other mutant beta globin genes. It is crucial that clinician do not assume the diagnosis but be mindful of these and carry out appropriate investigations to clinch the diagnosis. Especially in countries such as Maldives where significant number of cases of thalassemia still exist, the importance of this cannot be stressed enough. A summary of some of these are mentioned below.

1. Sickle beta+ thalassemia — Individuals with sickle-beta+ thalassemia have an illness that is less severe than HbSS disease. Disease severity is inversely related to the amount of HbA present, which varies from 5 to 30 percent. The peripheral smear shows the presence of hypochromic, microcytic red cells and levels of HbA2 are increased

2. Sickle beta0 thalassemia — Patients with sickle beta0 thalassemia have severe disease which may be somewhat less severe than HbSS disease. Unlike Sickle beta+ thelassemia no HbA is present on electrophoresis. It is distinguished from HbSS disease by the presence of hypochromic, microcytic red cells and increased levels of HbA2.

3. Sickle alpha thalassemia — The clinical manifestations and degree of anaemia in sickle alpha thalassemia are generally less severe than those seen in sickle beta0 thalassemia. HbA2 levels are increased according to the number of alpha globin gene deletions.

4. Sickle hereditary persistence of HbF (sickle HPFH) — Subjects with pancellular sickle HPFH are not anemic, do not suffer from vasoocclusive episodes, and may have HbF levels as high as 35 percent.

Conclusion

The above description and treatment of the disease is not exhaustive . There are several other considerations to be mindful in managing the disease such as addressing the issue of pregnancy, treating prolonged and stuttering priapism, reducing the risk of stroke. Regular renal function and cardiovascular monitoring with renal and cardiac imaging should be carried out. Also addressing the issue of iron overload, vaccination, vitamin supplementation and treating infections are all very important aspects of their care. When appropriate all patients should be assessed for pulmonary hypertension.

Sickle cell disease is a multi system syndrome and carries with it a huge emotional and financial burden. As clinicians we are at the forefront of helping these, often very young lives who endure a great deal, every single day and for that reason it is crucial that these patients get the right diagnosis and the correct treatment at every stage of their care.

References

- Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, Steinberg MH, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. Jun 9 1994;330(23):1639-44.

- Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, Shizukuda Y, Plehn JF, Minter K, et al. Pulmonary hypertension as a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. Feb 26 2004;350(9):886-9

- Pawliuk R, Westerman KA, Fabry ME, et al. Correction of sickle cell disease in transgenic mouse models by gene therapy. Science 2001; 294:2368.

- Mansilla-Soto J, Rivière I, Sadelain M. Genetic strategies for the treatment of sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol 2011.

- Wu LC, Sun CW, Ryan TM, et al. Correction of sickle cell disease by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Blood 2006; 108:1183.

- Nienhuis AW. Development of gene therapy for blood disorders. Blood 2008; 111:4431.

- Perumbeti A, Higashimoto T, Urbinati F, et al. A novel human gamma-globin gene vector for genetic correction of sickle cell anemia in a humanized sickle mouse model: critical determinants for successful correction. Blood 2009; 114:1174.

- Zou J, Mali P, Huang X, et al. Site-specific gene correction of a point mutation in human iPS cells derived from an adult patient with sickle cell disease. Blood 2011; 118:4599.

- Wambebe C, Khamofu H, Momoh JA, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised cross-over clinical trial of NIPRISAN in patients with Sickle Cell Disorder. Phytomedicine 2001; 8:252.

- Cordeiro NJ, Oniyangi O. Phytomedicines (medicines derived from plants) for sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; :CD004448.

- Fawibe AE. Managing acute chest syndrome of sickle cell disease in an African setting. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2008; 102:526.

- Oniyangi O, Cohall DH. Phytomedicines (medicines derived from plants) for sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; :CD004448.

- Iyamu EW, Turner EA, Asakura T. In vitro effects of NIPRISAN (Nix-0699): a naturally occurring, potent antisickling agent. Br J Haematol 2002; 118:337.

- SINGER K, SINGER L, GOLDBERG SR. Studies on abnormal hemoglobins. XI. Sickle cell-thalassemia disease in the Negro; the significance of the S+A+F and S+A patterns obtained by hemoglobin analysis. Blood 1955; 10:405.

- SMITH EW, CONLEY CL. Clinical features of the genetic variants of sickle cell disease. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1954; 94:289.

- Gonzalez-Redondo JM, Stoming TA, Lanclos KD, et al. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity in black patients with homozygous beta-thalassemia from the southeastern United States. Blood 1988; 72:1007.

- Gonzalez-Redondo JM, Kutlar A, Kutlar F, et al. Molecular characterization of Hb S(C) beta-thalassemia in American blacks. Am J Hematol 1991; 38:9.

Comments

No comments